Stay all summer

Everything ends, even this.

I'm embarrassed to admit when I heard Joshua Clover died my only context for his name was within my headcanon of critics from the '90s like Charles Aaron and Rob Sheffield. (Rest in peace Sacha Jenkins.) I was reading Sasha Frere-Jones' obituary of Clover when I got to a sentence, credited to Louis-Georges Schwartz, that stopped me in my tracks:

As a humanities scholar, as a pop critic, and as an artist, Joshua’s great contribution was trying to imagine audiences, readers, voices, and protagonists as collectives. Indeed, like his beloved Walter Benjamin, his method was to try to imagine them into existence.

Jones elaborates:

Why would Joshua’s awareness of the larger cohort be hobbled by something as obvious as taste? He did like what he liked but that was only in addition to and after he saw its value as a representation of some larger group.

I'd never seen my perspective reflected back to me with such clarity. It was an observation on a person whose work I am not familiar with as well as validation for my persistence in doing something I don't find comforting or easy or cool or lucrative but compels me anyway.

Collectives–mythical bodies of minds and persons in unconscious unison–has spoken to me since Jung, Campbell, and Catholic mysticism. It's influenced how I think about music and taste–this is where my fondness for Greil Marcus and David Thomson comes in. I worry my taste is neither deep, curious, or wide-ranging enough, yet I rebel against a label like "poptimist" because I don't relate to its exclusionary connotations. I also don't consider myself just a pop music fan, because "pop" papers over important distinctions between categories and implies genres I love like rap are incapable of pop. It also insinuates I am out here listening to C-tier Swedish artists in desperate need of a chorus fix to satisfy my basic desire.

I wrote in 2022 I engage with art and culture in terms of what it says about the time we're living in or the time it was produced–I respond to things instinctively, then figure out "why" after that. Artists are inspired and motivated by what they experience everyday, and when you zoom out (or in) you can learn about the culture, time, and people producing art, as well as who consumes it. Most of the time this happens in a scattershot way (progress isn't linear, people are unpredictable, etc.), and that's where "imagining" occurs.

For example I believe the hype around Sabrina Carpenter and Chappell Roan as year-of-our-Lord 2024 phenomena was mass delusion–people yearned for and craved a new pop star because we'd been beaten senseless by no-chorus, no-chord-progression, flat lite-disco since 2018, so they hallucinated saviors in these unremarkable stars. (They did the same thing when pop-punk was proclaimed novel in 2021, but that's forgivable as we were exiting a life-altering pandemic.) I've imagined a world (another way of saying it's my deep-seated, biased opinion) where people need something they don't have and locate a thing that most closely resembles it and lust after it hard. (This is sliding into Zizek territory but that's not my aim.) That Carpenter presents a dead-end, boring conversation starter for issuing a variant of Smell the Glove as an album cover is further proof she's a theoretical pop star rather than a musical one.

Joshua Clover — name another writer thinker teacher scholar who was in the streets like this. And who never failed to have the perfect song at the perfect moment. You can't. pic.twitter.com/rhFMb4b5Fk

— Joni (@poetryc0mmunity) April 28, 2025

The two other aspects of Clover's life–poet and community organizer–also struck close to home, especially as I've started a job in organizing. I'm convinced community organizing is the way out of everything–organizing is blocking ICE trucks from crossing the street, it's showing up for plausibly effective mass protests, it's pushing for local legislation, it's lobbying, it's even (in my opinion) direct service and mutual aid. Community organizing is inclusive. I don't understand the argument for example that harm reduction is not organizing. When people use resources to take care of each other because of institutional failure, that's community organizing.

I don't have a ton of smart things to say about Clover's work because I haven't had time to dig into it deeply, but I did breeze through the "Roadrunner" book and thought what he observed through Modern Lovers (and rock and roll and popular culture and cars and the industrial revolution writ large) was weightier than what is familiar to me. I found his observations metaphysical and alluring because he was not only a critic, poet, or organizer–he carried all those things. (It's never occurred to me that "Roadrunner" could be interpreted as a labor anthem.) It's more insightful than things we see arguing for historicity in music or pop culture simply by "going long," drawing a vague metaphorical or puddle-deep societal observation in it, then advancing some pointed, if not particularly original, criticism. ("Here's how XXXX predicted XXXX.") It's criticism through a lens of consideration and care, instead of consumer reporting or narrative-building.

Discovering Clover resonated not only because I was moved by what I was able to read but also because I've never figured out what I want to be, I know I can't be only one thing. Clover was also a professor. What would my lessons look like–sit with the enduring mysteries, miracles, and devastation of creation, and when compelled, start writing? Read this book, undergo traumatic personal transformation, and when compelled, start writing? What's on my syllabus–Our Band Could Be Your Life, The Brothers Karamazov, Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists? I could not be a serious teacher, so I'm interested in people who are writers in unorthodox ways (I don't mean trying to be Hunter S. Thompson).

Another writer I've been spending a lot of time with is Billy Woods. I had liked him from a distance but never fell in love until his most recent album (the name has use in history as a slur). I have found him to be too muscular and masculine, a sharp writer who hadn't yet tapped directly into my wavelength.

The movie poster logline for how the new album stirs me is it sounds like what 2025 feels like, and usually such reduction suggests reactionary, shallow art. But in this year of "flooding the zone" and the world's "richest" man firing public servants on a worldwide stage so stark it's made metaphors trite, Woods captures ambient terror so thoroughly it's disorienting and radicalizing in speaking truth to power, in witnessing as accountability, in language and storytelling as liberation. (It should be noted this album was most likely written, produced, and recorded well before the election.)

I don't call myself a "Marxist" or "Leninist" or "Maoist" because those terms signify a political identification that feels irrelevant to me, a Mexican-American from the Northside of Houston who grew up around fireworks and public school and Frito pie. (This ignores the practical implications of those movements on suburban Texan existence but I am talking about identity as opposed to policy.) I'd rather call myself a pacifist, writer, believer in equity and liberation. I'm an appreciator. Creation is an act–moving people through art is worship–when you speak to large groups of people, or tap into a shared feeling in the air–that's communal organizing.

Most analysis of Woods' album devolves into endless quotables, appropriate because it's astoundingly well-written. On the first song he says

The English language is violence, I hotwired it

I got a hold of the master's tools and got dialed in

on the next one he says

Had to do 'em greasy like cold spare ribs in the sallow glow of an open fridge

and on the next one–a riff on Misery–it's

Full moon, she came to me already wet with sex

Next day, I slept, head on the desk, dead tired

It's pass-fail on the test, it's bite marks on the breasts

and it keeps going like this for 18 songs, where summers are described as "the whole city just waiting" and he drops "best believe them crackers won't make it to Mars" and even drugs are bad now and twelve billion American dollars are hallowing out the Gaza Strip and Darko Milicic is a metaphor for institutional failure and he tells a story about a family eviction before Christmas that is depressing, gallows-tier-darkly funny, and self-incriminating–that cycle of emotions is very 2025. I am not having a terrible time because I'm on Twitter too much I'm having a terrible time because it's arrived next door and I'm fending for scraps and if I didn't have a sense of black humor or a kernel of strength I'd probably be run over, another victim of cruel, extractive capitalism. It's hard to imagine there will be a better album released this year.

I'm currently embarrassed by everything. I saw what could only be described as an "alternative" young person (tucked t-shirt, dad cap, wide-leg cuffed jeans, boots) in line at a coffeeshop with a pin on their backpack that read "oli-gargle my balls" and my reaction was...cringe? Not like, liberal cringe, or millennial cringe. More like, this is supposed to be funny, and, sure, but also, what does it serve to debase people in that way, and what are you communicating by it? Why am I reading this at 8:45 am? The message should be oligarchs need to lose their income, healthcare, loved ones, suffer bankruptcy, sit with their conscience, then succumb to starvation, because only then will reciprocal justice be served in relation to the injustice they've inflicted by extracting and accumulating so much capital all that's left behind is carcasses. That is my preferred message but it doesn't fit on a pin.

Kindness, dignity, and grace are what we should give each other, and "embarrassment" implies stoic, male-coded temperament that is harmful, so while "oli-gargle my balls" is embarrassing I also think, well, so is existence. Times are so debasing at this moment that every expression is painful. (A friend went to a No Kings march and reported seeing tearful adults recite the Pledge of Allegiance which, yikes.)

What I found inspiring about Clover as a critic is in caring about pop music his taste skewed populist, and his consideration of myths and other people tied into a pragmatic, but ultimately utopian worldview. Not that "poptimism" is inherently utopian but living so humanely you are inclined to assess what is speaking to the most people imaginable feels like care.

Something I've written about is how much my taste in music changed from the ages of around 10 to 13. I was too young to have had some formative sexual experience; I was not around people with advanced taste who told me stop listening to Wheatus and listen to Yo La Tengo. I simply read way too much, spent way too much time alone, and am deeply impressionable, so while my default as a literal child was to turn on the radio and enjoy what I heard, something made me dig deeper and discover another world.

What I gloss over in this story is I enjoyed listening to the radio in 1998. I have nothing but fondness for every single one of my memories of music videos (any channel, any genre, any time of day). Listening to the radio–pop radio, rap radio, rock radio. Listening to teenybopper shit with my sister–I owned the first Backstreet Boys CD, the one with "Quit Playing Games with My Heart." My older brothers were "cool," from the indie-rock leaning taste of my oldest brother (who still owned Counting Crows CDs) to the rap-heavy collection of my other brother (where Warren G sat atop Hum in his CD tower), and they were formative too, but not my only thread.

As the sibling closest to me in age (yet six years apart, a galaxy in child years) I spent the most time with my sister which meant I spent most of being 12 listening to Christina, Britney, and also Vertical Horizon. The cousins I was closest to are all girls–I loved every minute hanging out with them, discussing boy bands, being told what it meant to toss someone's salad, etc. Generosity and acceptance was in their girlhood, a world that can be more forgiving and inclusive and open than boyhood. I read every single issue of Seventeen and YM magazine for years, I read my sister's copy of Catcher in the Rye, we saw Incubus together in 2001 right after 9/11. As a high schooler then a college student then a young adult, I viewed this time as formative but inessential and not emblematic of anything about my tastes or preferences.

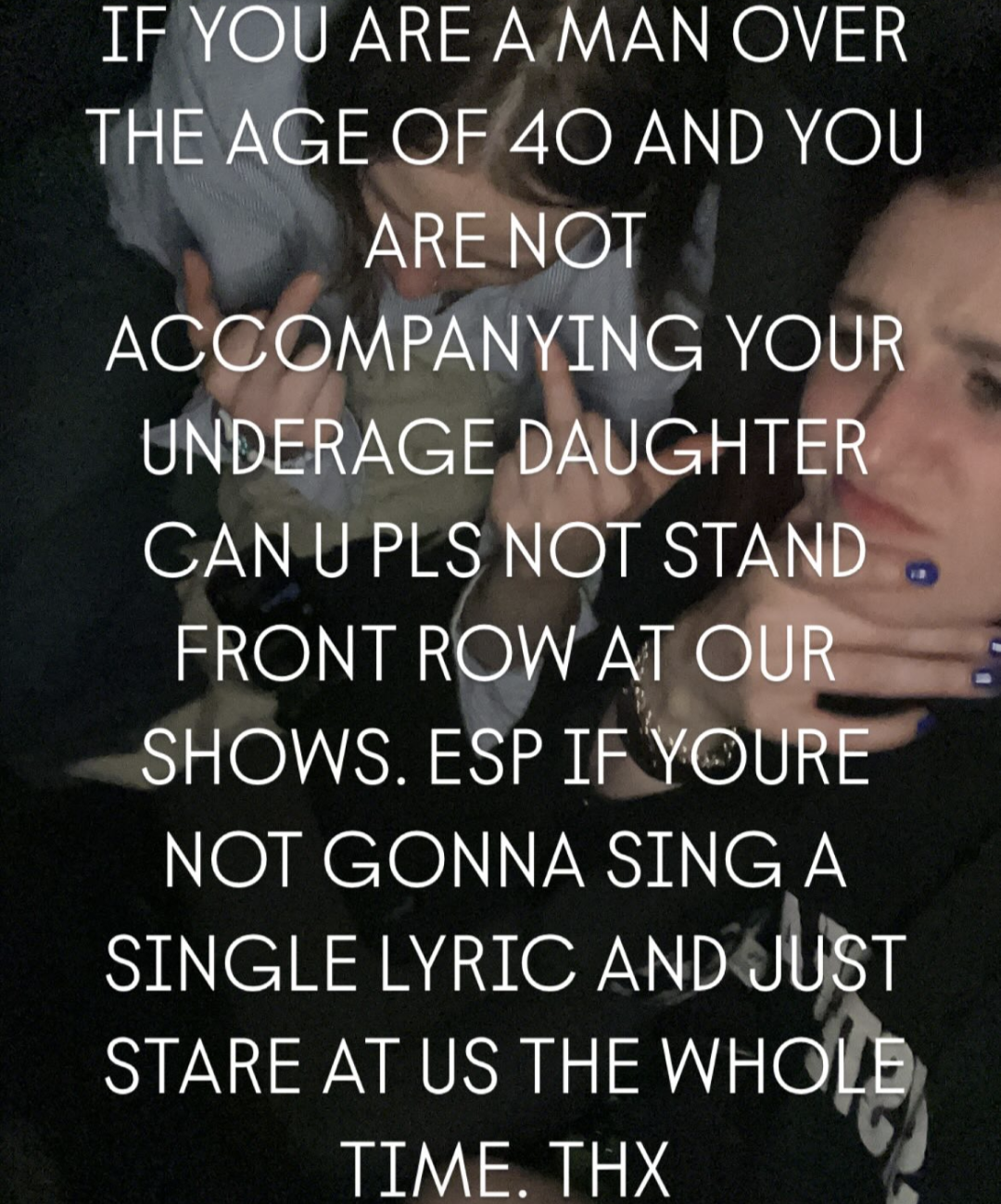

That is wrong. A critic loving pop music is no longer novel–in fact it's deeply embarrassing to imagine a 40-year-old man listening to Addison Rae (her album is good btw)–but curiosity about the kind of art a lot of people enjoy and respond to has always resonated. My tastes skew popular, and when I'm annoyed or unimpressed by someone like Jelly Roll I become prescriptive–actually, folks are wrong about this and here's why that's bad for the culture. Shit is spikier and more complicated than ever, so I no longer participate in that discourse. I don't listen to Morgan Wallen, never will, don't care about him as a cultural figure, never will, don't care that he's the most popular musician in the country, this country voted for Trump thrice, that means nothing to me. What's the real story? My thought instead is, "who cares about Morgan Wallen when Real Lies just dropped an album no one's writing about?"

I saw Momma a few weeks ago and it struck me I think they are my favorite band. Having a "favorite band" is like having a crush–the subtext is "this is my favorite band right now." I loved their 2022 record Household Name, but didn't love the advance singles they released ahead of April's Welcome to My Blue Sky. When it dropped I gave it a listen and was inclined to write it off as a minor disappointment. Gone was '90s-influenced guitar crunch and booming tom drums, in their place was slick, commercial pop rock. I thought the album was sleepy and I only loved one song, "Rodeo," which is a great piece of slick, commercial pop rock. Yet when I saw them live I thought—I love this album and this band because they are making slick, commercial pop rock. They graduated from 120 Minutes to the Buzz Bin and now they are on TRL. ("Last Kiss" suggests where they might go next– down the Farmclub.com wormhole.) I wouldn't want them to stay in the same mode for years, and now they're speed-running alt-rock after Nirvana with dizzying style and precision.

Anyone making rock music is performing a resurrection ritual of a genre ignited in the fifties, revolutionized in the seventies (rest in peace Sly Stone and Brian Wilson) and reached final form with nu-metal + rap rock in the nineties, when it fused with another genre entirely. When Limp Bizkit sold a million CDs in one week that was the ballgame (this is a neutral statement, Limp Bizkit hold a ton of value as a band). Momma recreates the radio of 1998, the last year before the airwaves became fully nu-metalized. They take it right back to where it all ended and do it again. Let's rewrite history, one fisheye lens at a time.

This "post-Nevermind" episode of Hit Parade nailed a thesis I've held in my brain forever but never heard someone else say: all those alt-rock songs of the late-'90s were just pop songs, and many of them were often great. The critical establishment was too preoccupied with authenticity, trying to taste-make a band like idk Quicksand into Nirvana, or parse what it meant to give a six-figure advance to Butthole Surfers. They failed to recognize we were in a years-long blitz of insanely well-written, catchy pop songs. Compare "Shimmer" or "Closing Time" to idk Benson Boone. The former are working on so many levels the latter is unaware of.

Welcome to My Blue Sky's promo-cycle lore about the two lead songwriters ending long-term relationships on the road as a story I might read in YM magazine in 2000 moves me. They exist at the intersection between my fondness for indie rock (democracy) and teenybopper shit (populism). I love "Stay All Summer" and involuntarily imagining the zoom-in on Devon Sawa in the music video. I love this reel of them saying that they are a pop band that writes pop songs–they're not doing the "from the pages of my diary" thing. I love that they took their immaculate hook-writing ability to a higher level. I loved tallying all the Black and non-white people at the show (a decent amount, including teen couples loving Mexicanly). I pray they don't want to be actors.

I was always fascinated by Sam Donsky's writing about The Killers, a band I don't like and never did–somehow his opinion on them mattered and that made them matter a little bit to me. I trust the taste of like five people and four of them asked me how was the Momma show. They are part of the story. I never thought deeply about why I liked their kind of music then and why I like it now but it has to do with likening great choruses to a mass of people moving and being moved by the same thing–you can call it worship or organizing or humanism, whatever the label is, it moves me.

What I'm reading: See Friendship

Listening to: Cartwheel

Watching: Eephus